Carlos Gonzalez Campo is a Research Analyst at 21Shares.

Crypto asset valuation remains an emerging topic seeking consensus, especially as the asset class expands and matures. Robert Greer, author of "What is an asset class anyway?" argues that assets that lack an objective measure of value and have a supply constraint are more vulnerable to irrational exuberance, citing the dot-com bubble as an example. Crypto assets lack an objective measure of value today among investors, similar to emerging tech companies in the late 1990s. We propose valuation methodologies that reconcile different approaches investors have taken in recent years.

We can value any asset using two approaches – intrinsic or relative. Intrinsic valuation measures an asset's value based on its capacity to generate cash flows. On the other hand, relative valuation methods, also called "pricing," estimate how much to pay for an asset based on what others are paying for comparable ones.

Investors might use a discounted cash flow method (DCF) to value a stock, but they wouldn't use that for a piece of fine art. Similarly, we must outline the various types of crypto assets to understand the differences we may expect in their value accrual and specific valuation approaches. In this regard, it's helpful to categorize crypto assets according to the three asset superclasses proposed by Robert Greer:

Like the Internet architecture, crypto assets and blockchain technology have two layers: (1) infrastructure and (2) applications. In his 2019 work, Chris Burniske categorized crypto assets at the infrastructure layer based on the consensus mechanism of the blockchain:

While we won’t delve too deeply into the application layer, we can apply the same first-principles thinking:

From the standpoint of a validator, PoS assets like ETH are akin to a stock paying a dividend yield, which means we can conduct a DCF valuation following four simple steps:

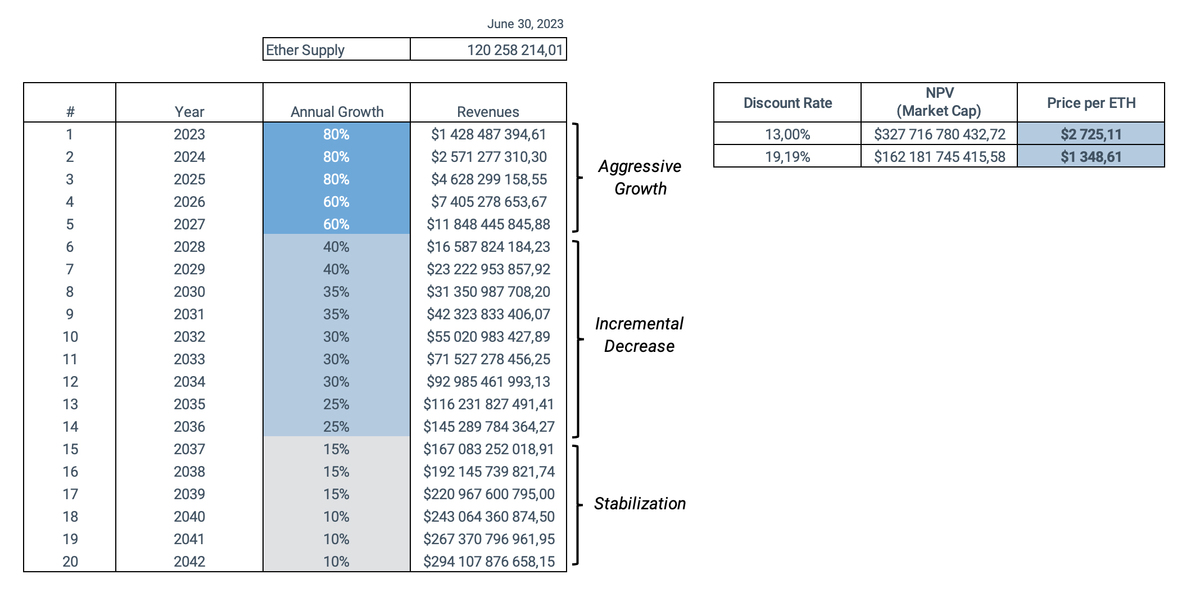

Assuming a discount rate of 13%, the implied price per one ETH today would be $2,725, a 60% increase from ETH’s current price (~$1,700). On the other hand, if we use a 19.19% discount rate, the implied price per ETH would be $1,349. Investors should interpret the results of this DCF valuation with caution and run their own assumptions. The rationale behind our approach was to be conservative and capture the high volatility of ETH in the discount rate to accurately reflect the asset’s riskiness. Another implicit assumption in our analysis is that the asset’s monetary premium (“Store of Value” component) is embedded into the DCF.

Source: 21Shares

A significant portion of equity valuations in traditional finance consists of relative valuations based upon market sizing and multiples, such as price-to-earnings (P/E ratio). This approach is more likely to reflect market perceptions and sentiment than a fundamental valuation. Moreover, investors can use relative valuations to "price" any asset, not just ones that generate cash flows. Although one can choose from an extensive set of multiples and comparables, for illustrative purposes, we'll concentrate on just one of the most actionable indicators for BTC.

The market-value-to-realized-value (MVRV) is a simple yet powerful on-chain multiple that leverages the transparency of the blockchain:

High MVRV values indicate a substantial degree of unrealized profits in the system. In contrast, values below "1" indicate that a significant portion of BTC's supply is near break even or at a loss. Historically, high MRVR ratios have coincided with BTC market tops, while values below "1" have preceded past cycles' bottoms.

There are various challenges and shortcomings regarding crypto asset valuations, such as insufficient historical data and complexities unique to the asset class.

For instance, the cash flows that PoS networks generate are not paid in fiat currency but rather in the native tokens of the network. This situation is as if Apple charged its customers in Apple shares instead of U.S. dollars. This unique feature creates a reflexivity problem because the dollar-denominated value of the revenue stream is directly dependent on the crypto asset's value.

We have provided investors with actionable methods to value crypto assets. The complexity and uncertainty of valuing this asset class might intimidate investors. However, it is worth remembering that the more uncomfortable an investor feels when valuing an asset, the greater the payoff of doing the valuation.