Jacob Shapiro serves as Head of Geopolitical & Macro Research and Senior Client Relationship Manager at Bespoke Group.

In an era of rising geopolitical volatility, wealthy individuals and families are reassessing where, how, and what they own. The age of unchallenged US dominance is over, replaced by a multi-polar world marked by fiscal recklessness, military confrontation, and political instability. As America’s golden age of investment fades, the country’s wealthiest are moving their money — and their lives — abroad in record numbers. Global diversification is no longer optional, but essential, for preserving wealth, lifestyle, and legacy in a world where opportunity is shifting beyond US borders.

Terms like high-net-worth individual, ultra-high-net-worth individual, and family office often obscure the individuality of the people and strategies they represent. As the saying goes, “If you’ve seen one family office, you’ve seen one family office.” Each manages generational wealth with distinct objectives and challenges. Increasingly, that wealth is on the move — between generations and sectors, and across borders.

According to data published in the Henley Global Mobility Report 2025, an unprecedented 134,000 millionaires relocated globally in 2024, a number that is projected to be surpassed by 8,000 in 2025. These flows are not straightforward, either — even while record numbers of US investors are looking abroad for a ‘Plan B’, the USA is among the countries with the biggest net inflows of millionaires from other countries.

As ever, the grass often appears greener elsewhere.

Borders, once symbolic, have regained meaning. Nation states — and the policies they enact — impact wealth whether one seeks them out or not. Resilience lies in acknowledging both the constraints and opportunities of geography — and planning accordingly.

Wealth brings optionality for those willing to embrace it. Preserving and growing capital is one piece of the puzzle; quality of life is another. We can make more money, but not more time — where and how you spend yours should be a conscious choice.

Decisions about how you own (planning structures), where you own (custody and private banking jurisdictions), and what you own (asset allocation) are increasingly consequential. In today’s world, thinking differently about liquidity and adapting portfolios to a multi-polar global reality are essential.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the only serious rival to US global dominance vanished. The fall revealed that the USSR had been more appearance than substance — economically weak and politically brittle. The USA, unshackled from Cold War constraints, exported its economic model globally, triggering an era of rapid growth, innovation, and capital accumulation.

This “unipolar moment” made investing relatively straightforward. The USA possessed unmatched military might, deep capital markets, legal stability, and eager consumers. Political polarization was low — both major parties generally supported free trade and restrained fiscal policy. By the late 1990s, the country was even running a budget surplus.

Global investors flocked to America. Demand for US treasuries seemed limitless. Some sought diversification in countries exposed to US-driven globalization — Germany for its exports, or China for its manufacturing capacity. But ultimately, investing in a US index fund and holding steady was the winning strategy. Even downturns like the dot-com crash and 2008 crisis proved, in hindsight, to be buying opportunities in an overall booming market.

That era is over. The first cracks appeared after 9/11. They deepened when Russia invaded Georgia in 2008 and further widened as Xi Jinping rose to power in 2013. The Brexit referendum in 2016 signaled a resurgence of nationalism. That same year, Donald Trump’s election brought ‘America First’ trade wars and escalating global tensions.

Covid-19 shattered any illusion of global cooperation. Wealthy nations hoarded vaccines and closed borders. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine was the final confirmation: the world had entered a multi-polar era.

During this period, the very foundations of US market strength began to erode. American military dominance waned. Populism and polarization fed on economic inequality. Once a champion of fiscal restraint, the US Government became a spendthrift under both parties, launching costly programs and entitlements.

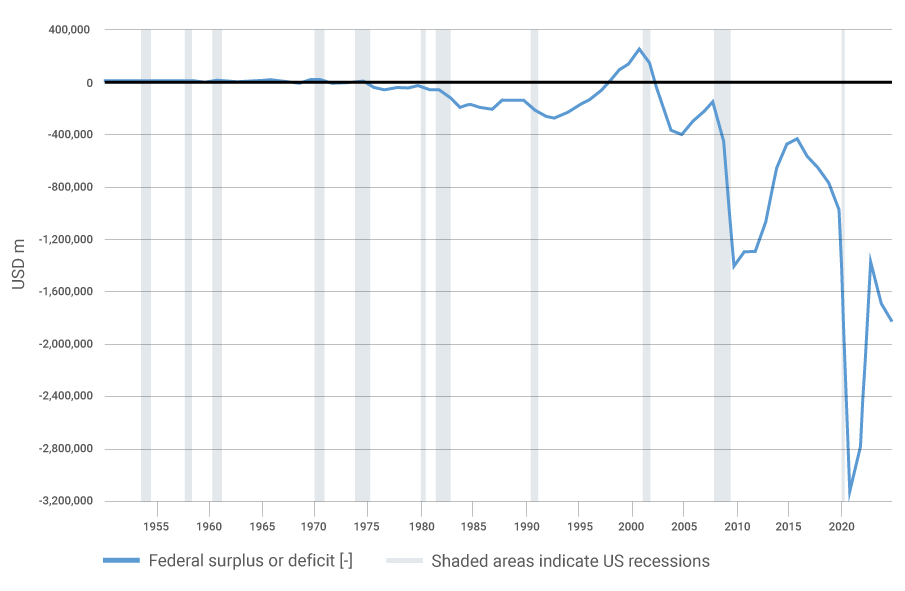

On the left, figures such as Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren rose in popularity by promising higher taxes on the wealthy. On the right, free trade lost favor to zero-sum protectionism. Both sides now support government expansion, even as US debt balloons to unsustainable levels. As the chart below shows, successive US governments of both parties have lost all pretense of fiscal conservatism.

Chart 1. An Ever-Expanding Fiscal Deficit

Source: U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Federal Surplus or Deficit [-] [FYFSD], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSD

Markets may be apolitical, but they aren’t blind. They reflect expectations about the future, not nostalgia for the past. Inflation has surged — driven not just by supply shocks but by years of unchecked spending. US debt service is now the government’s second-largest budget item, behind Social Security.

The US dollar remains the global reserve currency, but its dominance is being challenged. Countries are beginning to settle trade in their own currencies, hoarding gold, and turning to digital assets like Bitcoin. Confidence in US policy is eroding. Once-unthinkable scenarios — like a weakened navy failing to protect global shipping lanes — are now reality.

Investors can no longer count on Washington to prioritize sound policy or stable leadership. Political ideology has become a circle, where populism on the left and right ultimately meet at the point of fiscal unsustainability. Eventually, someone must pay the bill — and wealthy taxpayers are an obvious target.

America’s post-Cold War dominance created a golden age for US-focused investing. But the world has changed. Geopolitical power is more diffuse. Economic policy is more erratic. And quality of life — once a US advantage — is now rivaled or surpassed in many other regions.

For the first time in a generation, US investors must seriously consider that the best opportunities may lie beyond their borders. Strategic diversification, jurisdictional planning, and a reassessment of risk and reward are not just prudent — they are imperative. In the time of geopolitics, smart capital must go where the future is being built, not where the past once thrived.