Prof. Mehari Taddele Maru, is a part-time Professor at the School of Transnational Governance, and Academic Coordinator of the Young African Leaders Programme (YALP) at the European University Institute in Florence, and an Adjunct Professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, Bologna.

Africa’s richest individual, Aliko Dangote, needs 35 visas to travel in Africa, leaving him shackled by the very borders he sought to bridge with his vast business empire.

This perplexing paradox is all too familiar to Africans — a continent desperately seeking investors yet denying its citizens the freedom to move between its own borders. Even at home, nationals of African countries have limited destinations they can access without requiring a visa. According to the African Development Bank’s 2023 Africa Visa Openness Report, African travelers are required to obtain visas to visit 55% of other African countries. While there has been an improvement in e-visa availability in 28% of the countries, only four — Benin, The Gambia, Rwanda, and Seychelles — offer visa-free access to all Africans.

The irony is not lost on Africans as well as others: regardless of their wealth status, European visitors can travel across the continent with greater ease than Africans themselves, revealing the structural problems of visa regimes in the world. This irony further underscores how African states are unwilling or often unable to turn these artificial borders, relics of European colonialism, into integrative bridges that facilitate free movement for Africans. Dangote’s plight reminds us of the barriers that Africans face traversing their own continent, but these obstacles are even higher when applying for visas to travel to the Global North. Africans’ stark Schengen visa application rejection rate highlights that while the total number of Schengen visa applications from Africa decreased from 2.2 million in 2014 to 2.05 million in 2022, paradoxically, the rejection rate increased by 12%.

I would argue that weak economies and discriminatory policies based on identity and culture explain the high rate of rejection for African Schengen visa applicants. The nationals of countries with low gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and low gross national income (GNI) face a triple challenge: low passport power, higher visa rejection rates, and consequently, limited economic mobility. In short, the poorest individuals face the greatest difficulties when seeking to travel or move to more prosperous countries. Moreover, a number of my observations regarding the current prohibitive European visa regime for African Schengen visa applicants may also apply to other countries in the Global South.

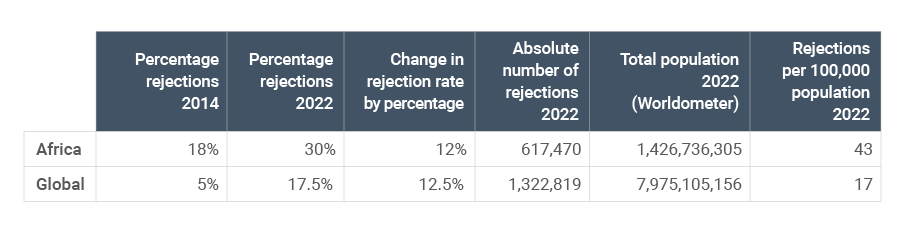

There was a 12% rise in the rejection rate of Schengen visa applicants from Africa between 2014 and 2022, which is slightly under the global average of 12.5% (see Chart 1). In 2014, the rejection rate for African Schengen visa applicants was 3.6 times higher than the global average, while in 2022, it was 1.7 times higher. This means 43 African applicants were rejected per 100,000 people, while globally, the rejection rate was 2.5 times lower at 17 applicants per 100,000.

Chart 1. Schengen Visa Rejections: Global versus Africa

Sources: “Short-Stay Visas Issued by Schengen Countries.” Migration and Home Affairs, 15 May 2024. home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/visa-policy/short-stay-visas-issued-schengen-countries_en; SchengenVisaInfo; “Overview of Schengen Visa Statistics (2014–2023).” SchengenVisaInfo, 5 July 2024. statistics.schengenvisainfo.com/; Worldometer

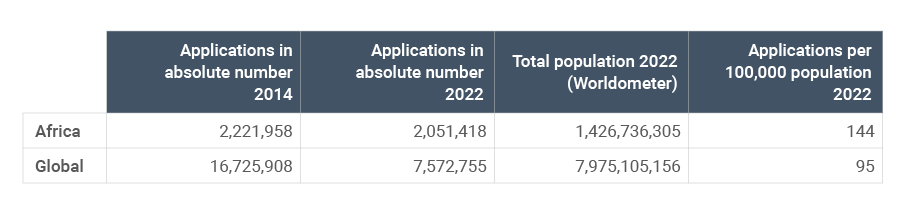

An explanation for the increase in rejection rates despite the decrease in the overall number of African applicants may be the heightened requirements and barriers for Africans post the 2015 'migration crisis’, which were reinforced by the additional restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic (see Chart 2).

Chart 2. Schengen Visa Applications: Global versus Africa

Sources: "Short-Stay Visas Issued by Schengen Countries.” Migration and Home Affairs, 15 May 2024. home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/visa-policy/short-stay-visas-issued-schengen-countries_en; SchengenVisaInfo; “Overview of Schengen Visa Statistics (2014–2023).” SchengenVisaInfo, 5 July 2024. statistics.schengenvisainfo.com/; Worldometer

Firstly, globally, the number of applications for Schengen visas has been declining over the years as rejection rates have surged.

Secondly, while restrictive for all applicants, the European visa regime is notably more stringent for African visa applicants than for those from other regions. In 2022, Africa topped the list of rejections with 30% or one in three of all processed applications being turned down, even though it had the lowest number of visa applications per capita. This was higher than the global average at 17.5%.

Thirdly, access to Schengen visas corresponds to the economic and passport power of the applicant’s country of nationality. The poorer the country of nationality, the higher the rejection rate. Many African countries have low ranking GNI per capita, and also rank low on the Henley Passport Index, which measures the number of destinations a passport holder can enter without a visa. A lower ranking correlates with a high level of rejection for Schengen visa applicants.

Fourthly, visa rejection is also being used as a condition for the return and readmission of illegal migrants in Europe. Visa sanctions are sometimes enforced by the European Council on African states that have a low rate of readmitting their nationals who are in the EU illegally. Essentially, it punishes African visa applicants due to citizens of the same state that are found to be illegally residing in Europe, and those with the lowest rate of return and readmission.

Lastly, and most importantly, while factors such as per capita income, GNI, the incidence of illegal overstays, and the low rate of return and readmission of Africans illegally present in Europe partially explain these higher rejection rates, they do not fully account for the significantly greater restrictions against African Schengen visa applicants, and, for that matter, the passport strength itself. It is highly likely that European migration policies, shaped by national identity politics, play a more significant role in these discriminatory restrictions than is officially acknowledged.

The above factors reflect European policies to contain migration from Africa, which undoubtedly has a significant impact on the partnership between Africa and Europe.

Globally, the absolute number of Schengen visa applications decreased from 16.7 million in 2014 to 7.6 million in 2022, representing a decline of almost 9 million applications. In other words, the global number of Schengen visa applications declined by nearly 54.7%. During the same period, the absolute number of Schengen visa applications in Africa decreased from 2.22 million in 2014 to 2.05 million in 2022, a decrease of almost 171,000 applications or 7.7%.

Nevertheless, despite the significant decline in both the absolute number and the percentage of Schengen visa applications, the rejection rate for Schengen visa applications increased significantly. Globally, the total rejection rate surged from 5% to 17.5% in 2022, marking an increase of 12.5%. In Africa, the rejection rate reached 30% over the same period, a 12% increase from the 18% rejection rate in 2014, and nearly twice the global average. About three in ten African Schengen visa applicants were rejected, compared to one in ten applicants worldwide.

Africa accounted for seven of the top ten countries with the highest Schengen visa rejection rates in 2022: Algeria (45.8%), Guinea-Bissau (45.2%), Nigeria (45.1%), Ghana (43.6%), Senegal (41.6%), Guinea (40.6%), and Mali (39.9%). By contrast, only one in twenty-five applicants residing in the USA, Canada, or the UK were rejected, and one in ten from Russia. As per the illustration, Algerians face a rejection rate that is ten times greater than that for those applying in Canada, while Ghanaians are four times more likely to be rejected than Russians. Nigerians face almost three times the rejection rate of applicants in Turkey (15.5) and twice that of Iranians (23.7)

Notable exceptions are the Seychelles and Mauritius, which along with 61 countries in Latin America and Asia are exempt from the Schengen visa requirement. A few African countries like South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia face a relatively low rejection rate of less than 7%.

Visa applications for various purposes, including work, study, and tourism, are subjected to lengthy and cumbersome application processes. Rejections are very costly for applicants, particularly the nonrefundable fees, but also transport and other expenses.

Officially, visa rejections are often attributed to doubts about applicants’ intention to leave the destination country before the visa expires. According to European states, most rejections are based on “reasonable doubts about the visa applicants’ intention to return home”. European visa policy grants wide discretion to consulates, potentially allowing for discrimination based on nationality and geographical factors. The criteria of “proof of intention to return home” in the Schengen visa regime is often linked to the economic status of applicants and their nationality.

With an elastic concept such as this, the Schengen visa regime, and likely other visa regimes of most middle- and high-income countries, allows immigration officials in the embassies and consulates housed in the Global South to effectively filter visa applicants based on their economic conditions and country of origin. Due to these key factors, some European countries, such as Ireland, that had visa-free arrangements for South African and Botswana passport holders have now revoked these arrangements to curb asylum seekers from poorer countries. In 2024, Irish officials found that “198 asylum seekers arrived in Ireland this year using South African passports” and that Zimbabwean and Congolese nationals are allegedly entering Ireland using South African passports.

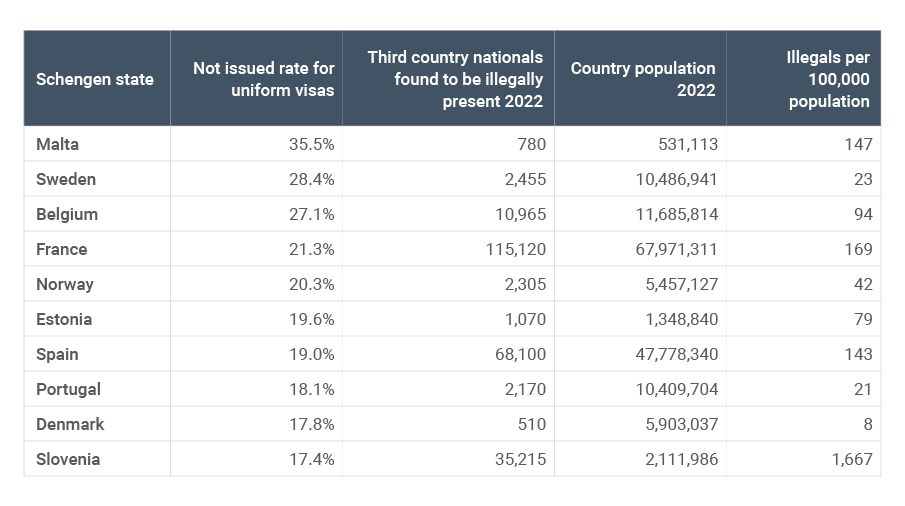

Malta, Sweden, Belgium, France, Norway, Estonia, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, and Slovenia are the top 10 European countries that have a high level of Schengen visa denials. The possibility of illegal overstay alone cannot account for the significantly higher rejection rates among African applicants. In 2022, Malta, with an alarming 35.5% visa rejection rate, only had 780 third-country nationals residing in the country without proper authorization, despite having only 147 illegally present migrants per 100,000 persons. In contrast, Slovenia, with 1,667 illegally present migrants per 100,000 persons, has a rejection rate of 17.4% (see Chart 3).

Chart 3. Top 10 European Countries with High Schengen Visa Rejection Rates

Sources: "Short-Stay Visas Issued by Schengen Countries.” Migration and Home Affairs, 15 May 2024. home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/visa-policy/short-stay-visas-issued-schengen-countries_en; SchengenVisaInfo; “Overview of Schengen Visa Statistics (2014–2023).” SchengenVisaInfo, 5 July 2024. statistics.schengenvisainfo.com/; Worldometer

There is no evidence to suggest that a higher rejection rate leads to a decrease in irregular migration or visa overstays. Visa requirements within the continent add to the challenges encountered by African applicants. The Henley Passport Power (HPP) Index, which ranks all 199 passports in the world according to the total percentage of global GDP each passport provides to its holder’s visa-free, reveals that the lower passport strength of many African nations further compounds the challenges faced by African applicants. Consequently, passports often hinder rather than facilitate mobility for Africans.

Proof of “intention to return home” is often linked to applicants’ economic status and nationality. It correlates with three factors: low GDP per capita, low GNI, and low HPP.1 These factors mean low economic mobility, which compounds the overall rejection rate of visa applications. Visa rejections are closely correlated with the GNI per capita of the applicant's country, disproportionately affecting poorer African nations.

The 2022 Q1 edition of the Global Mobility Report found that while democracy is not a strong predictor of global mobility, income reliably is. In a nutshell, countries with higher GDP per capita enjoy visa-free access to more destinations. Moreover, “citizens of low- and lower middle-income countries enjoy access to substantially fewer visa-free destinations than upper middle- and high-income countries”. Further research published in the 2023 Q1 Global Mobility Report revealed that a powerful passport is a conduit to economic opportunity and well-being. While low GDP (“poor country”) and low HPI (poor passport strength/visa-free access) mean poor economic mobility, this research adds that visa rejection rates correlate with Gross National Income (GNI), Henley Passport Index (HPI), and Henley Passport Power (HPP). The poorer the country of nationality, the higher the rejection rate. Low GNI (“poor country”) plus low HPI (poor passport strength/visa-free access) means poor economic mobility as well as a high likelihood of visa rejection rates.

Many African countries have low GNI per capita and also rank low on the Henley Passport Index, which measures the number of destinations a passport holder can enter without a visa. A lower ranking correlates with a high level of rejection for Schengen visa applicants. Visa regimes have inherent discriminatory tendencies based on nationality and the political-economic position of countries. At the center of this rise in visa rejection based on such an elastic concept is the rise of identity politics in Europe and elsewhere. Such an approach has immediate implications for European–African partnerships, including imposing barriers on efforts toward more trade and investment, education and health services, tourism, and legal pathways for labor migrants. This observation likely has broader relevance to some Asian and South American countries as well.

Nonetheless, nationals of countries like Equatorial Guinea (21.4%), Botswana (3.1%), South Africa (5.2%), Algeria (45.8%), and Namibia (7.1%), which have relatively higher per capita incomes, face rejection rates equal to or higher than those of the Russian Federation, Cuba, Croatia, Honduras, and Türkiye. One in two Algerian applications for a Schengen visa is rejected, even though Algeria has a higher per capita income than some countries with lower rejection rates.

The EU visa policy evaluates applicants’ travel intentions, and their likelihood of returning, and high rejection rates are utilized as a means of preventing illegal overstays. The granting of Schengen visas has increasingly served as an incentive for African countries to cooperate in the return and readmission of illegal migrants to Europe; consequently, the varying visa rejection rates among individual African countries may be attributed to the low rates of return and readmission by those countries.

Overstayers, classified as irregular migrants, are expected to return to their countries of origin. However, Europe is grappling with low rates of returning irregular migrants to their home countries, which has become a pressing political issue in many European nations. Effective return rates have consistently remained low, typically between 30% and 40% in recent years, before Covid-19. For migrants from certain major African transit and origin countries, the rates are even lower. These low return rates are linked to the challenges in fostering cooperation between African countries and the EU.

The return, readmission, and reintegration of African migrants with irregular status in Europe are among the most contentious policy areas in Africa–EU migration cooperation, with limited progress towards agreed-upon objectives. According to a research paper I co-authored, the effective return rate of irregular migrants in Europe (defined as the percentage of the number of non-EU migrants returned after receiving return orders, divided by the number of migrants issued with return orders), has consistently remained below 40%, particularly for African countries. The return and readmission rates of irregular migrants residing in Europe to their countries of origin are also lowest in the countries facing highest rejection rates. In 2022, the return and readmission rate for countries facing the highest rejection rates showed an average of 9%. Specifically, Guinea-Bissau had the lowest return and readmission rate at 3%, followed by Mali (3.1%), Guinea (4.6%), Senegal (5.8%), Algeria (7%), Nigeria (17%), and Ghana (18.5%).

While several factors can contribute to low return rates, including wars, international legal obligations to prevent sending migrants to places where they may face harm (the principle of non-refoulement), the lack of cooperation from some origin or transit countries is a significant factor. Since 2016, the EU has placed a strong emphasis on achieving swift and practical returns of migrants illegally staying in Europe.

From the perspective of African countries, the readmission of their citizens with irregular status in Europe is not a high priority issue, it poses complex economic and political implications. For many African nations, cooperating with the EU and its member states on return and readmission carries substantial risks, including a political backlash, negative media coverage, and a potential loss of support from the diaspora. Additionally, there are economic and social risks, such as reduced remittances and the impact on families' livelihoods and access to foreign currency.

The return and readmission of a large number of African migrants can be viewed as a political risk, considering the interests of both the migrants and the citizens who remain in their home countries. Insufficient funding and resources for reintegration support can contribute to resistance to return from both migrants and governments. African governments face opposition from affected families who have invested in the migration process, and whose livelihoods often depend on remittances. If there is a significant number of returnees but inadequate resources for their integration, there is not only public resistance to their return and readmission, but also from government branches responsible for employment and welfare. Given these varying interests, it is unsurprising that European efforts to establish readmission agreements with African countries have had limited success. Even when such agreements are signed, they may not necessarily result in increased return rates.

The factors mentioned above can partially explain the high rejection rate African applicants for Schengen visas experience. However, a deeper understanding of the underlying reasons for this high rate and the decrease in application numbers requires further investigation.

Politics and policies on national identity may provide a more comprehensive explanation for the situation. In political and policy circles in Europe and elsewhere, low (compared to Africa) fertility rates are cause for concerns about ethnic replacement. Recently, some European politicians have emphasized the need for increased births to reduce the reliance on labor migrants from Africa. Broadly speaking, Europe has been grappling with identity politics, particularly driven by far-right politicians, for some time now. This significantly contributes to the high visa rejection rate.

What do Schengen visa rejection rates reveal about the state of global mobility from Africa to Europe? While factors such as per capita income, national economy, applicants' income levels, credibility of return, and passport strength partially account for visa rejection rates, they do not offer a comprehensive explanation for the disparities with other regions. Passport strength and income levels alone cannot fully justify the variations in rejection rates for African applicants, as evidenced by the comparatively lower rejection rates for countries like India and Türkiye.

African countries experience exceptionally high rejection rates, some reaching as high as 45.8%, highlighting consistent discrimination and entry barriers, even for countries with significant economies and population sizes, such as South Africa, and per capita income, such as Gabon and Algeria. Furthermore, the discretionary nature of the EU’s visa policy, which assesses applicants not solely on individual merit and travel purposes, but also considers nationality, contributes to the overall discriminatory character of the current system.

In conclusion, the current European visa regime for African applicants seeking Schengen visas is excessively restrictive and exhibits discriminatory policies based on nationality. African visa applicants face more stringent restrictions compared to applicants from other regions, resulting in a disproportionately high rejection rate.

A significant priority for African countries has been to expand legal pathways for migration to Europe, including the creation of more extensive labor migration channels, especially for lower-skilled workers who currently face severe restrictions on their ability to migrate to Europe. In principle, the AU–EU partnership aims to facilitate increased legal and temporary mobility channels between Africa and Europe. However, the current visa application process and high rejection rates make achieving this goal nearly impossible. These high rejection rates, often unexplained, and restrictions targeting African applicants have a detrimental impact on Europe's efforts to foster strong partnerships between the private sectors of both continents. Visa restrictions and refusals also hinder private sector involvement in trade and business partnerships with Africa. These persistently high rejection rates run counter to Europe’s stated policy objectives and its commitment to facilitating legal pathways for Africans to migrate. Addressing these issues would signal Europe’s commitment to actively engage in business and strengthen trade relations between Africa and Europe.

As the EU seeks to enhance its geopolitical competitiveness, particularly compared to countries such as China, Russia, and certain African middle-power nations, initiatives aimed at promoting education and mobility between Africa and Europe become increasingly crucial bridge builders.

Discriminatory visa policies not only contradict Europe’s commitments to strengthening partnerships with Africa, but also undermine its relationship with and stated dedication to partnering with Africa.

The EU needs to address the current discriminatory practices within its visa application process and work towards promoting fair and equal opportunities for legal pathways to mobility between Africa and Europe. In light of these observations, the European visa regime needs to undergo urgent transformation to ensure fairness and accessibility for all applicants. Addressing disparities in acceptance and rejection rates, understanding the underlying reasons behind these differences, and fostering cooperation on return and readmission policies are critical steps towards a more equitable and inclusive visa system. Recent statistics on Schengen visa applications and rejection rates underscore the urgency of conducting a comprehensive review and reform of existing policies. Ultimately, such reforms are essential to promote equal opportunities and mobility between Africa and Europe, creating a more just and inclusive visa system that aligns with the broader goals of the Europe–Africa partnership.

Despite justifications based on security or economic concerns, the European visa system demonstrates apparent bias against African applicants. The current high and unequal rejection rates contradict Europe's professed commitment to stronger EU–Africa partnerships and exchanges. This undermines the AU–EU partnership and the goal of increasing legal avenues for Africans to travel and migrate to Europe. Significant policy changes are essential to address these disparities and reduce discriminatory and discretionary decisions in visa issuance.

Note

1 While the Henley Passport Index focuses solely on visa-free access, the concept of Henley Passport Power (HPP) encompasses a broader range of factors, such as economy and trade partnerships, diplomatic relations and international treaties (including free movement arrangements), consular services, and overall stability that contribute to the overall strength and influence of a country's passport.